October 2025

Food loss is food removed from the supply chain after harvest but before retail, without being consumed or repurposed for productive uses such as animal feed, seed, or bioenergy. Food loss is categorized into Pre-harvest losses, which occurs on the farm, typically before harvest, and Post-harvest losses, which take place after harvest during handling, storage, processing and transportation, up until the food reaches the retail stage. In contrast, food waste occurs further down the value chain, after food reaches consumers, whether processed or unprocessed, and is primarily caused by retailers, food service providers, and/or consumers themselves.

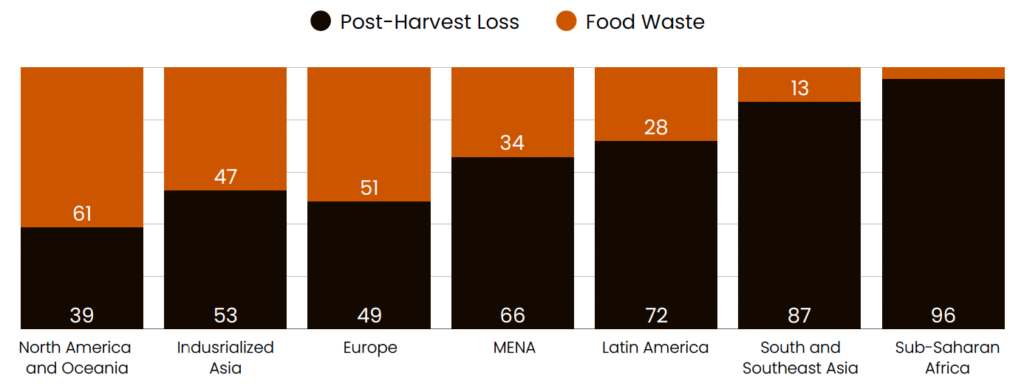

Food loss and food waste are global challenges, but they manifest differently across regions. In developed countries such as the United States, food waste is more prevalent, mostly due to consumer behavior, while in developing countries like Nigeria, post-harvest loss is more significant, highlighting underlying issues such as poor infrastructure, inadequate storage, and limited market access. The distinction is critical: Food waste reaches the consumers, thereby fulfilling demand to some extent, but in the case of post-harvest loss, food that has been produced does not make it to the consumer, leaving demand unmet and mouths unfed, resulting in food insecurity.

Fig 1: Post-Harvest Loss and Food Wastage by Region (% of Kcal lost and wasted), 2009

Of all the underutilized food in Sub-Saharan Africa, 96% is lost post-harvest, and only 4% is wasted after reaching consumers. On average, Sub-Saharan Africa experiences approximately 37% post-harvest losses, characterized by a similar pattern across different countries. Over the past five years, the average post-harvest loss for grains across Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda has been around 15.1%, with Kenya recording the highest (16%) and South Africa the lowest (12.5%).

Though these figures may appear moderate, their economic implications are substantial. According to FAO (2011), post-harvest losses in grains across Sub-Saharan Africa were valued at $4 billion, an amount sufficient to meet the annual food needs of over 40 million people. This figure is also comparable to the region’s annual grain import bill between 2000 and 2007, which ranged between $3 billion and $7 billion.

The situation is even more alarming for perishable crops such as fruits and vegetables. In Nigeria, post-harvest losses in tomatoes are estimated at 65%, comprising approximately 40% during harvesting and handling, 10–20% during transportation, and 5–15% during processing and storage. Similarly, a 2016 study reported 49% post-harvest losses in mangoes in Ghana.

Despite differences in staple crops across African nations, the patterns of post-harvest losses remain strikingly similar. Collectively, these countries have invested an estimated $8.58 billion in agricultural sector spending, yet these investments have not translated into meaningful reductions in post-harvest losses. For instance, Nigeria’s agricultural budget has increased by 196.4% over the last five years, while South Africa and Ghana have recorded budget increases of 104.17% and 29.63%, respectively. Unfortunately, these rising expenditures have yielded little tangible impact in addressing the persistent issue of post-harvest losses across the region.

Moneda’s report provides more insights on post-harvest losses across Sub-Saharan Africa, with emphasis on the gaps in Nigeria’s current storage systems. It also evaluates the economic and social implications of this challenge and outlines potential solutions and policy interventions.

Click here to download full report